What to Expect in a New York Sales and Use Tax Audit

For more than 40 years, Hodgson Russ attorneys have been called upon to help hundreds of clients navigate the confusing waters of a New York sales and use tax audit. The process tends to be long and arduous. Every client, no matter how sophisticated, has questions and concerns.

This booklet was written to give you an overview of the audit process and its legal foundations. We hope you find it helpful. The information is intended to be very general. We will be happy to answer your questions. Please don’t hesitate to call us or any member of our State & Local Tax Practice with your more specific questions.

| Mark S. Klein, Partner 646.218.7514 | Paul R. Comeau, Partner 212.751.4300 |

| Timothy P. Noonan, Partner 716.848.1265 | Christopher L. Doyle, Partner 716.848.1458 |

| Joseph N. Endres, Partner 716.848.1504 | Elizabeth Pascal, Partner 716.848.1622 |

| Andrew Wright, Partner 716.848.1254 | Joshua K. Lawrence, Partner 716.848.1622 |

| Debra S. Herman, Partner 646.218.7532 | Thomas J. Collura, Partner 518.433.2443 |

INTRODUCTION

For the attorneys in our State and Local Tax (SALT) Practice, sales tax is one of the most interesting, and challenging, taxes imposed by New York State. It’s interesting because it allows us to work with clients in every possible industry. Every business has to worry about sales tax compliance, no exceptions. Even if your business does not make sales subject to the state’s sales tax (like us!), no doubt you still make taxable purchases of goods and material used in the business (think desks, computers, paper, pens, etc.). Even tax-exempt organizations (charities, religious organization, etc.) have to worry about sales tax compliance because of New York’s convoluted, and often counterintuitive, rules governing exempt entities.

So New York’s sales tax affords us the opportunity to work with businesses of all shapes and sizes: from massive multinational conglomerates, to new startups in business incubators, all the way to local churches and charities.

WHY ARE THE STAKES SO HIGH?

We find New York sales tax audits to be among the most challenging because sales tax is one of the most aggressive taxes administered by the state. This aggressiveness stems from five issues that often arise during a sales and use tax audit:

- Taxability: you would think that knowing whether a transaction is subject to tax would be pretty straight forward. In practice, however, that’s not always the case. This happens frequently in technology and service industries (software, information, etc.), where New York’s statutory provisions cannot keep pace with technological innovation. We’ve seen many emerging-market businesses faced with significant audit liabilities because the auditors view the businesses’ sales as taxable, while the businesses themselves view their sales as excluded or exempt from tax.

- Audit Methodology: businesses making taxable sales are required to keep reasonable records of every sale they make. And courts often conclude that the records need to be

itemized so that every item sold (and the per-item price) can be identified. If they fail to keep such records, state auditors are permitted to use estimated methodologies to approximate the sales made by the businesses. Needless to say, such methodologies can

artificially inflate the taxable sales of a business, thereby increasing the amount of tax due under the audit. - Tax Pyramiding: if an auditor uses an estimated methodology to calculate additional sales, not only do these additional sales lead to a sales tax liability, but they can also lead to an income tax liability. If a business has more sales for sales tax purposes, the state may also take the position that it has more sales for income tax purposes as well.

- Penalties and Interest: although it fluctuates, as of January 2019, New York charges at least 10% interest (with daily compounding) on all sales tax liabilities. Moreover, there are numerous penalties that auditors can impose (substantial understatement, negligence, failure to file, etc.). Such penalties have a double impact. Not only is the penalty amount due, but if penalties are imposed, the interest rate increases to approximately 14.5%.

-

Personal Liability: sales tax is a trust-fund tax. That means businesses hold the tax in trust for the state until it is remitted with a return. Because of its trust-fund nature, sales tax is one of the few taxes that can lead to personal liability for those individuals who are responsible for running the business. Consequently, the state can seize the personal assets of those individuals who are deemed to be “responsible persons” to satisfy a sales tax liability. This trust-fund aspect even applies to taxes that weren’t collected (or held in trust) from customers and their corresponding penalties and interest!

WHY DID MY BUSINESS GET PICKED?

There are many ways New York State identifies businesses to audit. Random audits are becoming less and less frequent. If the NYS Tax Department chooses your business for audit, there’s a good chance it has some information that it wants to investigate.

For example, perhaps the Tax Department audited one of your business’s customers and no tax was charged on what appears to be a taxable transaction. This situation usually leads to an audit of the seller.

The Tax Department also utilizes technology to identify audit targets. The Tax Department maintains a highly sophisticated software program called CISS (Case Identification and Selection System) that analyzes information from various sources to find inconsistencies requiring additional investigation. The software runs the following analyses:

- A comparison of sales reported on income tax returns to sales reported on sales tax returns. These numbers don’t need to match, but they should be within a reasonable range.

- A review of a business’s taxable sales percentage as reported on its sales tax returns. Not all sales are taxable. Some items might be exempt (e.g., groceries, manufacturing equipment, etc.), while other taxable items might be purchased tax free by exempt organizations. Thus, the taxable sales of a business are typically some percentage of its total sales. The software analyzes this percentage to confirm that it is in line with similar businesses in that particular industry and geographic region. And because the taxable percentage of a business changes each quarter, it can tell if a business is just guessing by reporting the same percentage quarter after quarter.

- Identification of drastic changes in filing patterns. If a business stops filing returns, or there is a drastic reduction or increase in the amount of taxable sales, CISS may signal the Tax Department to investigate the change.

- A comparison of information provided in sales and income tax returns to information obtained from other sources. For example, financial institutions, insurance companies, franchisors, and liquor distributors have to file informational returns with the state. If, for example, the amount paid to an automobile repair shop by an insurance company exceeds the shop’s reported sales, an audit is likely. Similarly, if the liquor purchases made by a bar/restaurant exceed the reported sales of the business, an audit is likely.

- A comparison of a business’s statistics (e.g., total sales, taxable sales, cash to credit card ratio, etc.) against businesses in the same specific industry and given geographic area. Any statistical outliers are potential audit targets.

- An analysis of New York parking and speeding tickets issued to business vehicles to see if the businesses that own the vehicles are filing New York sales and income tax returns. This is particularly relevant for businesses from other states (CT, NJ, PA) that cross the border to service NY customers.

The Tax Department has indicated that CISS can run over 14,000 separate processes to analyze financial information and tax returns. Given the sophisticated information gathering and

processing now at the Tax Department’s disposal, if a business is not operating within what the computer views as “typical” parameters, it’s not a question of if the business will be picked for audit, but when.

DO OUT-OF-STATE BUSINESSES HAVE TO COLLECT AND REMIT NYS/NYC SALES TAX?

As a result of the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision in South Dakota v. Wayfair, states may require an out-of-state business to collect and remit their sales taxes so long as the business has a sufficient economic presence or nexus in the state; actual physical presence in the state is no longer required. In the Wayfair case, the South Dakota law required out of state businesses to collect and remit the State’s sales tax if the business had more than 200 transactions with South Dakota customers in a given year, or if the revenue generated from South Dakota customers exceeded $100,000 in a given year. Many other states have passed similar laws or rules, including New York.

New York’s Economic Nexus Rule

According to a Notice issued in January, 2019, out-of-state vendors with no physical presence in New York will still have to collect and remit sales tax on sales to New York customers if, during the immediately preceding four sales tax quarters:

- the business made more than $300,000 in sales of tangible personal property delivered in the state; AND

- the business conducted more than 100 sales of tangible personal property delivered in the state.

This rule was first articulated in a Notice published on January 15, 2019. However, because the Notice is based on provisions of the Tax Law that have been around for many years, the Tax Department has indicated that it is not required to apply this rule prospectively only. It may, in certain circumstances, seek to apply the rule retroactively to the date the Wayfair case was decided (June 21, 2018). It seems highly unlikely that the Tax Department could legally apply the rule to a date prior to the Wayfair decision.

What are the Limits of New York’s Economic Nexus Rule?

It is important to recognize that both the Tax Department’s Notice and the Tax Law apply these economic presence provisions exclusively to sales of tangible personal property. Thus, out-of state service providers with no physical presence in the state have a reasonable legal position that they are under no legal obligation to collect and remit New York tax. For example, if a New York customer purchases a taxable information service from a seller located exclusively out-of-state, the service provider appears to be able to sell the service without collecting and remitting the New York tax (of course, the customer has an obligation to pay use tax on the transaction).

But a word of caution is in order. As we’ll review in the next section, New York taxes software as the sale of tangible personal property (even if the software is remotely accessed and not actually transferred to the customer – i.e., a software-as-a-service model). Moreover, software is invariably used in conjunction with online services (for example, remote payroll processing, inventory tracking, business data management, etc.). Thus, any service that utilizes software that the customer accesses could allow the Tax Department to argue that it is taxing a sale of software (tangible personal property) and not the sale of a service.

It is important to note that because New York’s economic nexus rule establishes an “AND” test, out-of-state vendors can transact a significant amount of business and still not have a sales tax collection obligation. Here’s an example: let’s say I’m a high-end online art dealer or auction house with no physical presence in New York. The items I sell typically cost a couple hundred thousand dollars and up. But I only hold auctions sporadically throughout the year and have customers located across the country. In a given year I might make 50 sales to New York customers, the total amount of which will exceed several million dollars. Despite the high amount of revenue I receive from New York customers, I am not obligated to collect and remit tax on those transactions because while I am above the $300,000 threshold, I am below the 100 transaction threshold. And because New York’s economic nexus test is an “AND” test, I need to satisfy both parts before the state can obligate me to collect and remit.

Connecticut has a similar rule ($250,000 in sales AND 200 transactions, effective Dec. 1, 2018). This makes New York and Connecticut outliers. The vast majority of states impose an “OR” test similar to the law at issue in the Wayfair case (including New Jersey - $100,000 OR 200 transactions, effective Nov. 1, 2018).

WHAT TYPES OF TRANSACTIONS ARE SUBJECT TO TAX IN NEW YORK?

The New York State Tax Law imposes its sales tax on receipts from the following transactions:

- All sales of tangible personal property, including software that is actually transferred to the customer (e.g., via disk, hard drive, download, FTP, etc.) or remotely accessed by the customer via the internet (e.g., software-as-a-service), unless an exemption applies;

- Sales of utility services;

- Sales of specific enumerated services such as information services, installation and maintenance services, storage services, interior decorating and designing services, protective and detective services, and transportation services, to name a few;

- Sales of prepared food and beverages;

- Sales of hotel occupancy;

- Sales of many admission charges.

WHEN DOES THE SALES TAX ON A TRANSACTION BECOME PAYABLE?

New York’s sales tax is considered a “transaction tax” and a “destination tax.” This means that the liability for the tax occurs at the time of the transaction, not when the purchase price is paid. The transaction occurs when either there is a transfer of title or possession (or both) of tangible personal property, or when a service is rendered. The location of the change of possession or the rendering of the service determines both the incident and rate of tax. Thus, if a customer takes possession of the material in New York State, the tax is due at that point, at the rate set for the locality where the change in possession occurred. Consequently, sales to customers outside New York State where the customers take possession outside the state are not subject to New York sales tax.

WHAT TYPES OF AUDITS DOES THE TAX DEPARTMENT CONDUCT?

Broadly speaking, the Tax Department conducts two kinds of audits: (1) Field Audits, and (2) Desk Audits. The Desk Audit tends to be more limited in scope and usually focuses on a particular transaction (e.g., the purchase and use of a boat, the importation of goods from a foreign country that pass through U.S. Customs, the bulk sale of assets of a business, etc.). The Field Audit tends to be a more expansive review of every aspect of the sales and use tax compliance of a business. The Field Audit involves auditors “going out into the field” to visit the business being audited or the business’s representatives (i.e., the business’s accountant, tax attorney, etc.). This booklet will focus primarily on the issues that arise in a Field Audit.

HOW DOES AN AUDIT BEGIN?

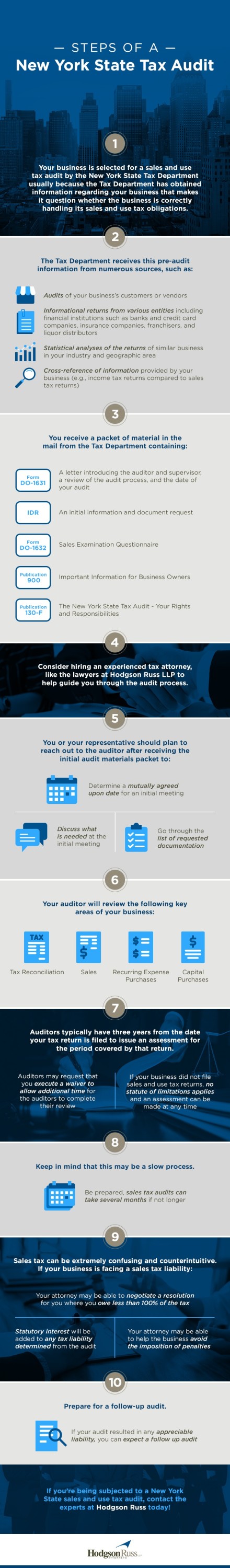

The audit generally begins with a packet of material that arrives in the mail from the Tax Department. This packet contains several items, including:

(1) A letter introducing the auditor and supervisor assigned to conduct the audit and a brief review of the audit process (Form DO-1631). In the first sentence, this letter proudly proclaims that “We’ve scheduled a Field Audit of your New York State Sales and Use Tax records.” It then informs the business that the auditor will be present at the place of business on a certain date to conduct an audit of the business.

(2) An initial Information and Document Request (“IDR”) that requests the following documentation for the audit period: sales tax returns, federal income tax returns, NYS income tax returns, a general ledger, a general journal and closing entries, sales invoices, all exemption documentation supporting nontaxable sales, a chart of accounts, fixed asset purchase invoices, expense and merchandise purchase invoices, bank statements, cancelled checks and deposit slips for all accounts, a cash receipts journal, a cash disbursement journal, the corporate book including minutes, board of directors and articles of incorporation, depreciation schedules and lease/rental agreements.

(3) Sales Tax Examination Questionnaire (Form DO-1632), asking various questions about the business operations (e.g., contact information, information regarding “responsible persons,” website information, product information, locations, invoicing procedures, typical sales volume and patterns, etc.).

(4) Publication 900, Important Information for Business Owners, which details a business owner’s sales and use tax responsibilities under New York Law (i.e., registrations, filing obligations, record keeping obligations, etc.).

(5) Publication 130-F, The New York State Tax Audit – Your Rights and Responsibilities, discussing various audit issues, including professional audit standards, statutes of limitations, privacy/confidentiality matters, etc.

DO I REALLY HAVE TO PROVIDE ALL THAT DOCUMENTATION ON THE DATE SPECIFIED IN THE INITIAL AUDIT LETTER?

The initial audit letter sets a date for the auditor to arrive at the business to conduct the field audit and the initial IDR contains a laundry list of documentation that must be provided at this visit. In practice, however, audits rarely unfold so neatly. The list of requested documents is voluminous and it could take months to compile the requested information. Further, the audit date may not work for the business. Normally, the best approach, after the commencement of the audit, is to contact the auditor,18 go through the laundry list of requested documentation, and discuss what is needed at the initial meeting to get the audit underway. In most audits, auditors do not review many of the records requested in the initial request letter. For example, we have yet to provide a corporate minute book in a sales tax audit. This initial conversation can streamline the audit process and save your business (and the Tax Department) significant time and effort. The conversation usually results in a mutually agreed upon date for the initial audit meeting, and a more manageable list of records that must be provided.

WHAT WILL AN AUDITOR REVIEW?

Just about every sales tax audit examines four key areas: (1) tax reconciliation, (2) sales, (3) recurring expense purchases, and (4) capital purchases. Below is a description of each section of the audit.

1. Tax Reconciliation

HOW DOES THE AUDITOR RECONCILE THE SALES TAX RETURNS OF A BUSINESS?

Initially, the auditor needs to verify that every single dollar of tax collected by the business was remitted on the sales tax returns of the business. Normally, the auditor can resolve this issue by reviewing the tax returns and the vendor's sales tax accrual account to determine whether the numbers match up. This initial aspect of the audit is fairly straightforward and usually resolved

during the first audit meeting.

WHAT TYPES OF RECORDS WILL AN AUDITOR REVIEW WHEN EXAMINING THE SALES OF A BUSINESS?

The types of records that will be reviewed will depend on how the business operates. For example, cash businesses such as bars and restaurants will be required to produce daily, transaction-by-transaction cash register tapes (not just the nightly summaries) or point-of-sale data (if the business utilizes a computerized sales system) for the test period. Businesses that bill customers for payment will have to provide general ledger accounts detailing the sales transactions and copies of corresponding contracts and invoices.

2. Sales

IS AN AUDITOR REALLY GOING TO REVIEW EVERY SALES TRANSACTION DURING THE AUDIT PERIOD?

The review of sales is designed to ensure that the business is reporting all taxable sales made during the audit period and to confirm that the tax is being calculated correctly on all sales. Though the business can require the auditor to review every sales transaction that occurred during the audit period, it is usually preferable to allow the auditor to review a test period (typically a quarter during the audit period) and then extrapolate any liability found during the test period to the rest of the audit period. This approach can dramatically shorten the duration of the audit by limiting the number of issues that need to be discussed. If this “test period” method is chosen, the auditor will request a “Test Period Audit Method Election” form to be completed by the business. This form confirms that the taxpayer has consented to the use of the test period methodology, though it does not obligate the business to accept the audit results.

Auditors are instructed to choose a test period that seems representative for the audit period as a whole. Auditors generally avoid the quarter or month with the most or least amount of sales, choosing instead to review an “average” sales volume month. This is because the auditor’s extrapolation must fairly represent the liability that would be found if the auditor had reviewed all of the sales of the business. If it does not, the business can challenge the audit results. For example, if the sales of a business are seasonal, a test period from the busy season would result in an inaccurate estimate. Another possibility is that an unusual transaction might occur in a test period that does not occur elsewhere during the audit. Such transactions require either a separate, special extrapolation, or removal from the test period altogether.

Generally speaking, it is best for the business for the test period to be as representative as possible (i.e., few, if any, anomalies as described above) and for it to contain as few sales tax billing/collection errors as possible. Keep in mind that the amount of sales in the test period may not be a good indicator of the eventual liability. Some businesses incorrectly assume that the higher the sales volume, the higher the eventual liability, and the lower the sales volume, the lower the eventual liability. In fact, the opposite can be true. For example, a test period with high sales volume and few errors can create excellent audit results, whereas a test period with low sales volume and many errors will likely result in a high audit liability.

Once the test period review is complete, the auditor will provide the taxpayer with an “exceptions list” that details all transactions where tax was not collected but should have been (or where tax was collected, but at the wrong rate). The taxpayer is then afforded the opportunity to review these transactions to demonstrate either that tax was not due or that tax was, in fact, remitted to the state. Every transaction that is removed from this list reduces the ultimate liability of the business.

Once the exception list is set, or if the parties cannot agree on all of the transactions contained on the list (this happens in disagreed audits where the vendor will appeal the audit results), the auditor will take the liability found during the test period and extrapolate it to the rest of the audit period to determine the total sales liability due. Auditors can use different extrapolation methodologies to arrive at the final liability total. The most frequent methodology employed by auditors involves the auditors creating an error rate by dividing the tax liability found during the test period by the total sales revenue for the test period. That error rate is then applied to the total sales revenue per quarter to calculate additional tax due per quarter, and ultimately the final sales tax liability. However, auditors can extrapolate using other methodologies and metrics.

WHAT ISSUES ARISE REGARDING TAX EXEMPT SALES?

It might seem counter-intuitive for auditors to spend time reviewing transactions that are exempt from tax, yet every sales tax audit includes a review of these transactions. Auditors review exempt sales because, if an auditor finds a problem with the basis for the exemption or the exemption documentation, the transaction will automatically create a tax liability.

As part of the auditor’s review of the sales of the business, he or she will examine the exemption documentation obtained by the business to substantiate its tax exempt sales. The most frequent exemption that is reviewed is the resale exemption, but many other exemptions could apply.

Under New York's rules, a business that accepts a timely and properly completed exemption certificate in good faith is relieved of the burden to collect the sales tax from the customer, even if it is later determined that the transaction was indeed taxable. Thus, for an exemption certificate to provide protection, it should satisfy the following three requirements: (1) the certificate should be properly completed – in other words, every box or line that can be completed, should be completed; any blank sections may invalidate the certificate; (2) the certificate should be timely received (usually within 90 days of the transaction), and (3) the certificate should be accepted in good faith – this means that the seller accepting the certificate cannot have any “actual knowledge” that the certificate is being misused.

This last requirement raises many issues. For instance, sometimes auditors take the position that a business’s acceptance of an exemption certificate was not in good faith because the transaction was ultimately one that was subject to sales tax for one reason or another. Here, however, the rules are heavily weighted in favor of the vendor. Indeed, unless it can be shown that the vendor had actual knowledge that the exemption document issued by the purchaser was false or fraudulently presented, no tax can be assessed against the vendor. In other words, the Department has to prove that the vendor knew that the materials being purchased were not subject to the claimed exemption (e.g., a purchaser provided a resale certificate but the vendor knew the materials were not going to be resold). It is important to note that “mere suspicion” that the exemption does not apply is not enough. A vendor can accept an exemption certificate in good faith even if it suspects the exemption doesn’t apply, but has no actual knowledge to that effect.

Also, sometimes sellers simply fail to obtain exemption certificates (such as resale certificates) or the certificates on file are not properly completed to the satisfaction of the Tax Department's auditors. Even in those cases, however, the failure to have a proper resale certificate does not transform an otherwise nontaxable transaction into a taxable one. The Tax Department’s regulations allow the seller to prove the applicability of an exemption by other means of evidence, such as a statement from the purchaser, shipping records, bills of lading, and so forth.

WHAT TYPES OF ISSUES ARISE WHEN REVIEWING AN AUDITOR’S EXCEPTION LIST?

When reviewing an auditor’s exception list, a vendor should consider several issues that may require the auditor to remove the transaction from the list. Here is a list of issues that should be considered:

- Is the transaction subject to an exemption or nontaxable under the Tax Law?

- Did the customer take possession of the goods or use the service outside of New York State? This is a frequent issue in software transactions or sales of information services where the customer may access the products from locations both inside and outside the state.

- Did the customer self-assess use tax or was the customer previously audited by the Tax Department for the same period? If so, the transaction should be removed from the audit because the state cannot collect the tax twice.

3. Recurring Expense Purchases

In reviewing recurring expenses, the auditor is looking to confirm that the business paid tax on purchases of materials, supplies, and services that recur throughout the audit period. Purchases of materials, supplies, paper, pencils, services, or anything else that a business purchases on a regular basis, or at regular intervals, and does not list on its depreciation schedules, normally qualify as recurring expenses.

To figure out the scope of review, auditors will usually examine a vendor's chart of accounts and select some purchase and expense accounts for which invoices have to be provided. Once again, a test period is typically employed to reduce the amount of time and work involved in the audit. During this part of the review, businesses should be on the lookout for refunds. Often businesses will pay sales tax on nontaxable or exempt items simply because they showed up on their supplier's bill. Also, businesses often pay full tax on their purchases of goods that ought to be partially taxed (e.g., software used in multiple states, electricity service partially used for production, etc.). If those issues show up in the test period, they should be added in as a negative adjustment, and one subject to the overall extrapolation, which could significantly reduce any liability found on audit.

The audit will then proceed in the same way as the sales portion of the audit discussed above. The auditor will create an exception list of transactions where no tax was paid and the vendor will have the opportunity to review those transactions to see if they should be removed from the list. The auditor will then extrapolate the test period liability to the rest of the audit period in a similar method as discussed in the sales review above.

4. Capital Purchases

The last area of review concerns the vendor's purchase of capital items or fixed assets. Because those purchases are not of a recurring nature, and are typically not too voluminous, an auditor will normally review each and every capital transaction during the audit period in detail to determine whether the vendor correctly paid tax. That's right -- every purchase over the three-year audit period will have to be examined. Generally, the vendor should have a general ledger account for its fixed assets in different categories, and auditors will want to see the detail and invoices in those categories for the entire audit period. Normally, auditors will also request copies of the taxpayer's depreciation schedules because normally assets listed on those schedules would constitute fixed assets. The review of the depreciation schedules also allows the auditors to double-check to make sure that all fixed asset information is being provided. Because auditors typically review each fixed asset purchase in detail, no extrapolation is necessary here.

IS AN AUDITOR REQUIRED TO BASE THE AUDIT RESULTS ON THE RECORDS OF THE BUSINESS?

Under well-established rules, a business is required to maintain adequate records detailing its sales and purchases. If it does so, it is entitled to have those records used to complete its audit.In other words, if a business maintains adequate records, auditors are required to limit their review exclusively to those records. Computer-assisted statistical sampling of the taxpayer’s records is considered by the Tax Department to satisfy this requirement.

However, if a business does not maintain adequate records, the law permits the auditor to determine the amount of tax due based on "such information as may be available," and external indexes may be used if necessary. Case law in this area also makes it clear that exactness in the method used by the Tax Department is not required. Instead, the Department need only adopt an audit method that is reasonably calculated to determine the amount of tax due. If the business wants to contest the audit conclusions, the burden is on the business to demonstrate, by clear and convincing evidence, that the audit method employed was unreasonable.

WHAT QUALIFIES AS ADEQUATE RECORDS FOR SALES?

According to the Tax Department, businesses must keep records of every sale made during the audit period, the amount of the sale, and the sales tax on the sale. If applicable, businesses must retain a true copy of each:

- sales slip, invoice, receipt, contract, statement, or other memorandum of sale;

- guest check, hotel guest check, receipt from admissions such as ticket stubs, receipt from dues; and

- cash register tape and any other original sales document (and not just a nightly summary – you need a transaction-by-transaction itemized register tape).

If no written documentation is given to customers, businesses must keep a detailed daily record of all cash and credit sales in a daybook or similar journal.

Moreover, if the business sells both taxable and nontaxable goods or services (most businesses do), it must identify on the invoice or receipt which of the items sold are subject to sales tax and which are not. For example, a cash register tape must list each item sold with enough detail to determine whether that item is subject to sales tax. The business must always separately state the amount of sales tax due on the invoice or receipt that it gives to its customer.

Finally, if the business delivers the product or service to a place other than its place of business, it must maintain records that prove where delivery took place.

WHAT QUALIFIES AS ADEQUATE RECORDS FOR PURCHASES?

According to the Tax Department, records must be maintained to establish the taxable status of all purchases of property or services. Purchase records should include records related to:

- purchases subject to state and/or local taxes,

- purchases for resale (e.g., inventory and raw materials), and

- purchases exempt from state and/or local taxes for reasons

other than for resale

Purchase records must substantiate all of the expenses of the business and its cost of goods sold. These records should also show that the purchases made by the business bear a reasonable relationship to its business sales. The business should also keep any other record or document that, given the nature of the business, would be necessary to prove that it has collected and paid the proper amount of sales or use tax due. This typically includes all invoices and schedules used to remit use tax as part of the sales tax returns of the business.

WHAT TYPE OF INDIRECT AUDIT METHODS CAN AN AUDITOR USE IN THE ABSENCE OF ADEQUATE RECORDS?

Auditors are trained to employ a number of different indirect audit methodologies depending on the industry involved and the facts of the particular case. For example, auditors can conduct an observation test where they observe the business operations one or a few days and extrapolate the taxable sales observed during those days to the audit period. Auditors can also conduct a purchase markup audit, where they obtain the purchase records from the suppliers of the business and then determine a markup percentage from the price list or menu of the business. The auditors can then calculate the total amount of sales for the audit period based on this information. Regardless of what method an auditor chooses, these methodologies are inherently inaccurate and frequently based on unfounded assumptions. Businesses should strive to maintain adequate records so as to avoid these indirect audit methods.

WHERE SHOULD I HOLD THE AUDIT?

We generally recommend that the audit be held at a neutral site, away from the business, such as the office of your accountant or attorney. This eliminates a few possible avenues of misunderstanding. First, if the audit is conducted at the business, auditors might be able to discuss the audit with random employees who do not fully understand all aspects of the business operation. Second, it tends to limit the auditors from being able to conduct a fishing expedition where they request significantly more documentation than they would have had the audit been held at a neutral site. In other words, it tends to focus the audit, which, in the long run, tends to be better for both the Tax Department and the business. It also avoids the possibility of disruptions that might influence productivity.

SHOULD I EXECUTE A WAIVER ALLOWING THE AUDITORS ADDITIONAL TIME?

Auditors typically have three years from the date a return is filed to issue an assessment for the period covered by that return.26 This is an issue that comes up in most sales tax audits due to the amount of time that the audit takes and because, unlike income tax returns, which are filed annually, sales tax returns are generally filed quarterly. Thus, a statute of limitations typically expires every three months.

As a result, more often than not businesses choose to execute the waiver and allow the auditors additional time. If the business refuses to execute the waiver, the auditors will likely create a rushed assessment based on information in their possession at the time. On appeal, the auditors will likely claim that they weren’t given adequate time to conduct the audit so they are not to blame for any inaccuracies in the results.

During the appeals process businesses typically work with the auditors to arrive at a more reasonable assessment (if any), but this more confrontational approach often results in the auditors taking aggressive positions. There are many decisions during the course of the audit that are left to the auditor’s discretion. By taking an aggressive stance with respect to the waiver, the business can expect many of these discretionary issues to be decided in an unhelpful way.

There is, however, one situation where a waiver should be refused. If the business is responsive to the auditor’s inquiries, and timely provides the documentation requested, but the audit is dragging on for an excessive amount of time, the waiver can be used to spur the auditor to conclude the audit. Remember that the longer the audit takes, the more the business will have to pay in interest on any resulting liability. So an auditor’s delay is literally costing the business money. If the auditor has been given a reasonable amount of time to conduct the audit, a refusal to execute a waiver should be considered.

Finally, keep in mind that the Tax Department has an informal policy of not opening an audit for any period that is set to expire within 60 days of the expiration of the statute of limitations.

HOW SHOULD I COMPLETE A RESPONSIBLE PERSON QUESTIONNAIRE?

A responsible person questionnaire is a document that provides the auditors with information regarding the individuals responsible for running the business. This is an important document because if the audit results in a liability, the Tax Department may personally assess some or all of the individuals listed in the questionnaire. Sales tax is one of the few taxes that can create personal liability for the individuals running the business. Thus, extreme care should be taken when completing the questionnaire.

WHAT IF MY CUSTOMER ALREADY PAID THE TAX?

Sellers and purchasers are legally both liable when sales tax is not collected on a particular transaction. However, what if the Tax Department is asserting tax on an item a seller sold to a purchaser that was already audited? The answer is that New York's overlapping audit rule should provide some relief. Under that rule, if the seller is able to show that its customer was subject to a sales tax audit for the same period, it can request that the transactions with those purchasers be removed from the audit and vice versa. The state should not be able to get the tax twice on the same transaction!

CAN I COLLECT THE TAX FROM MY CUSTOMER FOLLOWING THE AUDIT?

Sellers that complete a sales tax audit and pay tax on transactions that were not taxed at the time of sale are permitted to contact their customers to seek reimbursement. New York law permits a seller to seek reimbursement of the tax from its customer as if the tax was part of the original purchase price. Under New York law, the statute of limitations for contract claims is six years, so presumably a vendor has six years from the date of the transaction to recover the tax from its customer. Of course, customer relationship and other practical business considerations might make it unwise to pursue customers for sales tax on old transactions.

HOW LONG WILL THE AUDIT TAKE?

The audit’s duration depends on the number of issues raised and transactions reviewed. Sales tax audits tend to be slow processes. The accumulation and analysis of the documents can take months. Auditors cannot be hurried in their review of documents. Discussion and negotiation can drag on for weeks or longer.

DID YOU SAY NEGOTIATION?

Yes. Many audits are resolved for less than 100% of the tax that the Tax Department claims is due. Our ability to negotiate a resolution will depend in large part on the quality of the documentation available.

WILL INTEREST BE CHARGED ON ANY TAX THAT IS DUE?

Yes. In most circumstances statutory interest will be added to any tax liability determined as a result of the audit. Interest rates change quarterly but have been generally in the 7% - 10% range in recent years. However, if penalties are assessed as part of the audit, the interest rate jumps to roughly 14% - 14.5%.

WILL PENALTIES BE ASSESSED?

This depends on the facts of the case. If it is the first audit of the business, the business maintained adequate records, and the tax liability is comparatively small, there is a good chance that penalties will not be assessed. However, the New York Tax Law provides for the imposition of penalties for failure to file, failure to pay, substantial understatement, and/or negligence and fraud. During the negotiation process, we will always pursue the abatement of such penalties as a condition for settlement of the case.

WHAT ABOUT POST-AUDIT PERIODS?

The NYS Tax Department is like a stray animal; if you feed it, it will keep coming back. So if the audit results in any appreciable liability, you can expect a follow-up audit.

To avoid a contested follow-up audit, many businesses choose to ask the auditors to update the audit period to bring it to the present. This way any mistakes that created liability during the audit period can be corrected going forward, and the resulting liability from those mistakes can be put to rest by bringing the audit up to the current period. This affords the business a clean bill of health when starting the next audit.

We hope that we have provided you with a useful overview of the New York State sales and use tax audit process. We will work closely with your accountants and in-house tax personnel to achieve the best possible result for your business. Please don’t hesitate to contact our State & Local Tax Practice at any time to discuss your questions or any issues related to your audit or future tax planning.